Grandma came from a long line of shutterbugs. We have generations of family portraits, wedding photos, baby pictures, and candid shots going back over a century. She had photographs of her childhood pals, girls like Deanne Greathouse and Cleo Gray, whose names formed the fabric of my Roosevelt County folklore.

In my twenties, when her house was an easy drive west on 84 and over the Cacouate Road, I visited every month or two to clean her house and spend time with her. My favorite part of these visits was after supper, looking through the photo albums and scrapbooks she kept on a floor to ceiling shelf at the end of the hallway, while the Lawrence Welk Show played in the background. During one of these visits I noticed, on the page opposite a ticket stub for Little Orphan Annie was another ticket stub. I couldn’t tell what it was for, so I carried the book to Grandma’s chair and perched on its arm as I showed her the ticket.

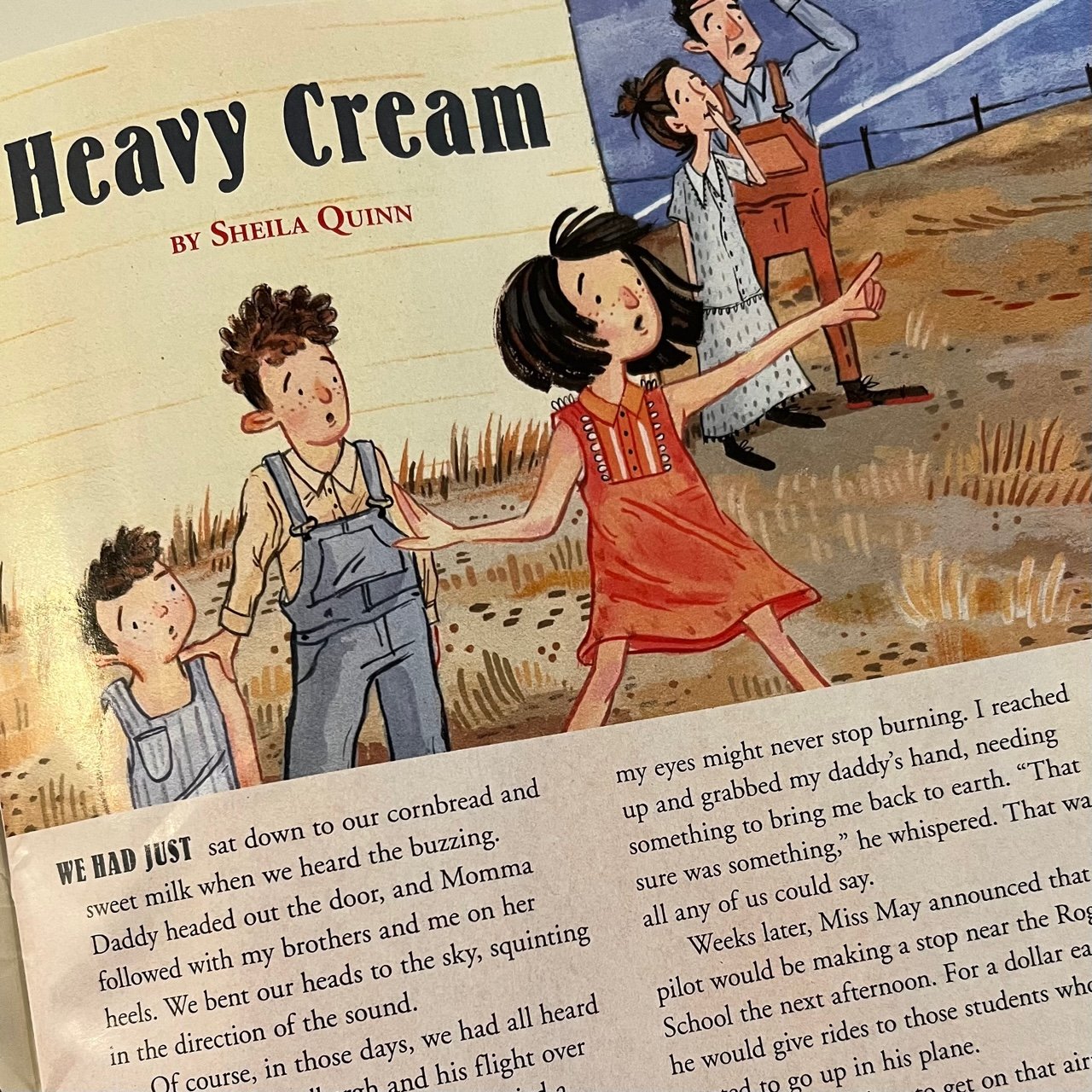

It took her a minute. She looked at the rest of the page and the cover of the scrapbook. Then she told me a story about the time in grade school when a pilot came and offered the children rides in his airplane for a fee. She said not many of the children could afford it, but her father wanted her and her brother to ride. She didn’t remember where they’d got the money.

I was stunned. Little Orphan Annie came out in 1932 when Grandma was only eight years old. Orville and Wilbur had gone up in their plane only thirty years before. And a pilot in a plane just showed up?

My modern sensibilities couldn’t grasp this. As a teacher, I couldn’t imagine what that school day was like. As a parent, I couldn’t imagine allowing my young daughter to go up in a plane without me. Or at all.

Grandma had a wistful look, but she didn’t seem to think this was extraordinary. It was just another story from her quiet life.

The next time I talked to my mom, I brought up the story, assuming she’d heard it a million times.

She’d never heard it.

She was shocked both by the story and by the fact that it as news to her. We pressed for details but Grandma couldn’t recall much more.

It was a decade later before I was hit with a sense of urgency. If we didn’t start collecting Grandma’s stories and preserving them somehow, they would disappear when Grandma died. Dementia would take them even faster.

Grandma was in a nursing home now and I’d started collecting her stories, not knowing yet what I would do with them. Mom visited Grandma’s brother, Gordon. He was four years younger than Grandma and his memory was holding out better.

She asked him about the time the airplane came. He was puzzled. He’d never heard that story either. He chalked it up to Grandma’s dementia. “You know, she doesn’t remember things. Her mind gets confused. That’s all that was.”

When mom delivered this report, I found myself being defensive. “But this was years ago, before the dementia. And I saw the ticket stub,” I told her. He’s wrong. It had to have happened. Maybe he was just too young to remember. After all, he wasn’t the brother who also got to ride. But surely he would have heard about it. Wouldn’t it have been a story they would retell?

Unfortunately, the scrapbook had disappeared by this time. In the process of cleaning out Grandma’s house, all of the photo albums had been digitized but no one recalled seeing the scrapbook. I was the only one who had heard the story of the pilot and the plane ride. Among all of the aunts, uncles, cousins, nieces, and nephews, no one recalled hearing anything about it. Now I started wondering whether I was losing mymemory. Had I been mistaken?

I tried to corroborate Grandma’s story. I checked archives of the local newspaper. I emailed local librarians and historians at the town’s university. No one had any information about this sort of thing happening. I added the bits I knew to a running Word document of her stories I was collecting.

I think of these stories like classifications of shrinking animal populations. They’re labeled vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered based on how many of the species are still alive. There were some family stories we all knew. How Andy’s ear was bit off and how I cried all the way from Lovington to Portales because I wanted to get to Grandma’s house. These would be considered of “Least Concern.” If Grandma’s pilot and plane story was a species, and I was the only one still holding it, the story was near extinction. I tried to get the story to spread, but without the scrapbook and without corroboration from Grandma’s brother, people were skeptical.

“It might have happened to someone she knew.”

“Maybe she saw it in a movie.”

“She was probably confused.”

They didn’t believe the story. They didn’t believe me and Grandma. The story would hit the extinction list if no one believed it.

Fortunately, this story doesn’t end there. In fact, it’s only the beginning.